Dr. Mardy's Quotes of the Week ("The Pursuit of Happiness")

April 20—26, 2025 | THIS WEEK'S THEME: “The Pursuit of Happiness”

Opening Line of the Week

After first reading these words, I set the book down for a moment to reflect on Harris’s opening salvo—which, for all practical purposes, might be called the pursuit of unhappiness.

I immediately found myself thinking of the many unhealthy things people do for pleasure—drinking, smoking, drugging, overeating, or binge shopping—but that almost always result in unhappiness. As Harris continued, though, he surprised me by identifying one culprit that hadn’t occurred to me:

“Many of us spend our lives marching with open eyes toward remorse, guilt, and disappointment. And nowhere do our injuries seem more casually self-inflicted, or the suffering we create more disproportionate to the needs of the moment, than in the lies we tell to other human beings. Lying is the royal road to chaos.”

For nearly 2,000 memorable opening lines from every genre of world literature, go to www.GreatOpeningLines.com.

This Week’s Puzzler

On April 11, 1908, this man was born in Lodz, Poland (then in the Russian Empire). Only three years old when he emigrated with his family to the United States, he grew up in a working-class neighborhood of Chicago. From childhood, he spoke Yiddish as well as English, and he remained proficient in both languages for the rest of his life.

An avid early reader and an exceptional student, he graduated with a political science degree from the University of Chicago in 1930. After graduation, he taught English part-time to immigrants while continuing his graduate studies (he eventually received his Ph.D. in 1937). It was during his night school classes that he met a student who would inspire him to write one of the era’s most endearing works of fiction: The Education of H*Y*M*A*N K*A*P*L*A*N (1937).

The novel was an engaging tale about a Jewish immigrant struggling to learn English in night school (the title came from the idiosyncratic manner in which the central character signed his name). The novel alone was a significant literary work, but it was The Joys of Yiddish (1968) that made an invaluable contribution to American culture. It was because of this book that words like chutzpah, kibitz, nosh, schlep, kvetch, and zaftig became a part of the American English lexicon.

In his long and distinguished career, this week’s Mystery Man offered memorable observations on countless topics, including this one:

Who is this person?

Has “The Pursuit of Happiness” Guided Your Life?

The quotation in this week’s Puzzler appeared in an article titled “Words to Live By: The Real Reason for Being Alive.” In the piece, this week’s Mystery Man continued:

“Happiness, in the ancient, noble sense, means self-fulfillment—and is given to those who use to the fullest whatever talents God or luck or fate bestowed upon them. Happiness, to me, lies in stretching, to the farthest boundaries of which we are capable, the resources of the mind and heart.”

I was a college junior when I first came across these words—and I was so impressed that I hand-copied them on a 3-by-5-inch index card. I’d only recently begun the practice of formally collecting inspirational quotations, and I quickly tacked the card on a bulletin board above my desk. Every day for months, it was the first thing I saw when I sat down to study—and it is no surprise that it ultimately morphed into a kind of personal credo.

About ten months later—and less than a month before President John F. Kennedy’s assassination—I recall JFK making a nearly identical point. When asked in a 1963 press conference if he liked his job, he replied:

JFK’s off-the-cuff remark was an impressive demonstration of a well-read man who was completely at ease in discussing complex subjects. It also showed that he was a pretty good student of history, for his response closely resembled a passage in Edith Hamilton’s The Greek Way (1930), a book that was part of Harvard’s curriculum when JFK was an undergraduate in the 1930s. In her book, Hamilton cited “an old Greek definition of happiness” that went this way:

“The exercise of vital powers along lines of excellence in a life affording them scope.”

Quotations like these have an almost universal applicability, but they especially resonate with Americans because ours is the only nation that includes “the pursuit of happiness” in its founding documents:

These are among the most famous words ever written on any subject, and it is fitting that they originally appeared in one of history’s most important political documents. Primarily drafted by Thomas Jefferson, a young Virginia delegate to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, the document was written to formally express the American colonists’ grievances against the government of King George III, to formally sever ties with England, and to establish a new democratic republic in North America.

In an 1825 letter to a friend, Jefferson wrote that his intention in drafting the document was not to create something new and original, but rather to craft something that “was intended to be an expression of the American mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion.” About the Declaration, he went on to add that “All its authority rests then on the harmonizing sentiments of the day.” By this, he meant the powerful ideas he found in books from his favorite philosophers, heard in conversations with his fellow legislators, or learned about in his correspondence with friends and colleagues.

If you’ve ever wondered where Jefferson got the inspiration for his famous line about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, you have to go no further than John Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690). Locke was one of Jefferson’s favorite philosophers, and he was almost certainly familiar with these two passages from Locke’s famous essay:

“The necessity of pursuing happiness is the foundation of liberty.”

“[Man] hath by nature a power…to preserve his property—that is, his life, liberty, and estate.”

I believe these two passages were among the chief “harmonizing sentiments” of the day that Jefferson found so inspirational. He simply melded them together, and in doing so, expressed the core ideas of freedom and liberty more eloquently than anyone else in world history. The life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness conception was not simply a soul-stirring creation, though, it was the very first time that pursuing happiness was declared a fundamental human right. It was a dramatic leap forward in human governance.

Having said this, though, I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that pursuing happiness is also one of the greatest stumbling blocks to actually achieving happiness. There are two reasons why this is true.

Problem #1: Confusing Pleasure with Happiness

The first problem occurs when people confuse pleasure with happiness. While these two states overlap, they are not the same. Pleasure is a fleeting quality that is focused on what might be regarded as the antithesis of long-term happiness: immediate gratification.

In pursuing pleasure, we’re looking for a quick fix. That’s why we turn so reflexively to our pleasure-of-choice when we’re stressed, lonely, depressed, bored, anxious, or emotionally overwhelmed. A drink, a toke, or a pill takes the edge off. An eating binge brings comfort. A shopping extravaganza lifts us out of the moment of despair we don’t want to be in. But the problem with all forms of pleasure-seeking is that they offer a flash of relief, and then vanish. For a moment, we’re fooled into thinking we’re okay, but over time, we’re left feeling numb rather than nourished.

I’ll have more to say on hedonism—the formal word for a life of pleasure-seeking—in a future issue. But for now, all you need to know on the subject was expressed by one of history’s greatest thinkers more than sixteen centuries ago:

The second major problem associated with the pursuit of happiness was beautifully described by yet another of the world’s great philosophers:

If we had to give the problem a brief name, we have several alternatives, but one of the best might be expressed this way:

Problem #2: Happiness is not Found if Directly Pursued

The second problem is reflected in one of history’s great paradoxes: when happiness is pursued directly, it almost always fails. The question then becomes, if we’re not going to directly seek happiness, what should we be pursuing? Happily, Mill provides the answer. We should, he says, pursue the happiness of others, the improvement of mankind, and even some art or pursuit. In other words, we should pursue something that will benefit others around us or the larger world in which we live. The legendary Viktor Frankl expressed the same idea far more succinctly in the Preface to a 1992 edition of Man’s Search for Meaning:

“Happiness…cannot be pursued; it must ensue.”

It is now almost universally accepted that one of life’s most tragic blunders is pursue happiness for its own sake. If, however, you focus your energy and your efforts on something else—like a higher or deeper or more meaningful life—your chances of experiencing happiness increase dramatically.

The pursuit of happiness remains, at its core, a beautiful human endeavor. But we must be clear—and wise—about how we go about seeking it. Otherwise, we risk turning a noble idea into a lifelong disappointment.

This week, take a few moments to think about what happiness means to you. And if you’d really like a challenge, imagine yourself standing at a lectern before a throng of reporters, as President Kennedy did in 1963. Suddenly, someone shouts out, “How happy are you in your current life? And can you give us an idea about what happiness means to you?” Okay, go ahead, give it a try. And after you do, take a few moments to peruse this week’s compilation of quotations on the topic:

No human being can make another one happy. — W. H. Auden

Absorption in things other than self is the secret of a happy life. — James Cagney

That is happiness; to be dissolved into something complete and great. — Willa Cather

If you want to live a happy life, tie it to a goal, not to people or objects. — Albert Einstein

Happiness Makes Up in Height for What It Lacks in Length. — Robert Frost, title of poem

The search for happiness is one of the chief sources of unhappiness. — Eric Hoffer

A happy life consists not in the absence, but in the mastery of hardships. — Helen Keller

Happiness consists in finding out precisely what the “one thing necessary” may be, in our lives, and in gladly relinquishing all the rest. — Thomas Merton

But O, how bitter a thing it is to look into happiness through another man’s eyes! — William Shakespeare

The way to choose happiness is to follow what is right and real and the truth for you. You can never be happy living someone else’s dream. Live your own. And you will for sure know the meaning of happiness. — Oprah Winfrey

For source information on these quotations, and many, many others on the topic of HAPPINESS, go here.

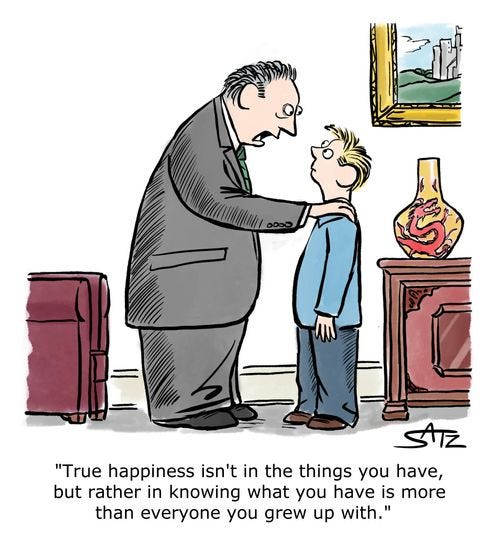

Cartoons of the Week:

Answer to This Week’s Puzzler:

Leo Rosten (1908-97)

Dr. Mardy’s Observation of the Week:

Thanks for joining me again this week. See you next Sunday morning, when the theme will be “Anxiety.”

Mardy Grothe

Websites: www.drmardy.com and www.GreatOpeningLines.com

Regarding My Lifelong Love of Quotations: A Personal Note

Mardy, I admire the comprehensive way you’ve covered the topic of happiness. I’ve always thought that seeking happiness was like trying to squeeze a wet bar of soap; it’s not an end in itself, but a byproduct of something else like serving others or achieving goals. Reflecting on the Thomas Merton quotation: Happiness consists in finding out precisely what the “one thing necessary” may be, in our lives, and in gladly relinquishing all the rest. I have found that the “one thing necessary” changes. Like Merton, the “one thing necessary” for the first part of my life was religion, being a priest. The I left the priesthood and married and the one thing necessary changed. Now that I am a widower, I am seeking what is necessary at this stage of my life to bring the same happiness I experienced earlier. Thanks as always for your insights.

"Ours is the only nation that includes 'the pursuit of happiness' in its founding documents."

That's true, but the kingdom of Bhutan put its focus on "gross national happiness" (as opposed to an economic focus on gross domestic product) in its constitution in 2008. Bhutan's king first suggested that shift in focus in 1972, to conform with Bhutan's 1,000 year culture of Buddhism, based on the idea that "happiness is accrued from a balanced act rather than from an extreme approach." The idea is not pursue happiness directly, but to focus on nine domains that will indirectly bring happiness.

I always thought that Buddhism focused more on suffering than happiness but I guess happiness comes when nirvana (satori in Japanese) is achieved, since that gives liberation from suffering. The idea that happiness cannot be sought directly -- that "happiness pursued eludes" -- resonates deeply with Buddhist teachings, especially in Zen Buddhism. Zen emphasizes that enlightenment or satori cannot be grasped through direct striving or attachment, but instead comes naturally when one lets go of desires and expectations, embracing the present moment fully.

Zen teacher D.T. Suzuki told a fable about a woodsman who came upon a beaver who promised him satori if he killed him with his ax. The woodsman tried many times to kill the beaver but every time he struck at him the beaver would sense the blow coming and dodge it. Finally the woodsman went back to chopping wood and as he brought the ax down on a log the head flew off and killed the beaver. The woodsman achieved satori.

The woodsman's repeated attempts to kill the beaver symbolize the futility of forcing enlightenment through sheer effort. It is only when he returns to his ordinary task — chopping wood with no attachment to the outcome — that the unsought happens and satori is achieved. This reflects the Zen idea that enlightenment often comes when one is least expecting it, in the midst of simple, mindful actions.

This story also aligns with the Zen koan tradition, where paradoxical or seemingly nonsensical tales are used to transcend logical thinking and awaken deeper insight. It's a reminder that the path to true happiness or enlightenment is not about chasing it but about cultivating a state of openness and presence.