Dr. Mardy's Quotes of the Week ("Self-Praise")

September 8—14, 2024 | THIS WEEK'S THEME: “Self-Praise"

Opening Line of the Week

The opening words come from the title character, a fourteen-year-old beauty named Josephine Oaklin—and, given the foreshadowing quality of so many first sentences, the reader has every reason to believe that some unfortunate effects of boasting will re-surface later in the novel.

In the opening paragraph, Josephine continued:

“Boasting’s practically the same as bragging, and both are incredibly vulgar.”

Like Lolita (1955), Image of Josephine portrays a middle-aged man’s obsession with a beautiful young girl, but without the dark and unsettling sexual energy of Nabokov’s novel. By contrast, Tarkington’s novel explores the tragic consequences of idealization, obsession, and fixation.

By the way, I’m now getting into high gear on “The Best Opening Lines of 2024” (this will be my fifth end-of-year compilation, and you can find links to all of them here). If you’d like to nominate any candidates, e-mail them to: drmardy@drmardy.com.

For nearly 2,000 memorable opening lines from every genre of world literature, go to www.GreatOpeningLines.com.

This Week’s Puzzler

On September 13, 1938, this woman was born in Washington, DC (she celebrates her 86th birthday this week). As a result of her father’s job as an economist for the United Nations, she grew up all around the world. After graduating with an English major from Wellesley College in 1959, she moved back to Washington, DC, where she took a job as a “copy girl” at the Washington Post.

Over the years, she worked in a variety of jobs at the paper: embassy reporter, White House social reporter, and theater/movie critic. She also co-founded the paper’s “Style” section in 1969. In 1978, she began writing an advice column titled “Miss Manners.” About the moniker, she said:

“I made myself Miss Manners. It was like Napoleon: You crown yourself because nobody else can do it.”

While this week’s Mystery Woman is regarded as one of history’s most famous etiquette columnists, her advice was wide-ranging, and often went well beyond the boundaries of social manners. On the subject of self-praise, she offered two memorable observations.

Who is this person? (Answer below)

What Role Has “Self-Praise” Played in Your Life?

Nearly all human beings desire admiration and respect, and many think the best way to achieve this goal is by “selling” themselves to others, almost as if they were “pitching” some kind of commercial product.

As the first quotation in this week’s Puzzler reminds us, though, rather than proclaiming our own good qualities, it’s generally far better to let other people discover them on their own. The second quotation adds an additional—and most intriguing—suggestion: if you’re going to engage in self-promotion, do it in such a subtle manner that it actually looks more like humility

Despite these caveats, some of you might still reasonably argue, “Why not praise ourselves? After all, we’re in the best position to know our positive attributes aren’t we?” This idea has been expressed many times over the centuries, but never better than in these two observations:

Self-praise is the formal term for a practice that is commonly called boasting or bragging. Writing in his Nicomachean Ethics (4th c. B.C.), Aristotle described the practice as a kind of theft or larceny, in which the boaster or braggart “lays claim to creditable things which do not belong to him.” Here’s how the two terms are defined in the American Heritage Dictionary (AHD):

“Boast. To glorify oneself in speech; talk in a self-admiring way.”

“Brag. To talk boastfully; arrogant or boastful speech.”

In a Usage Note, the AHD editors suggest that bragging is the more offensive behavior, writing: “Brag implies exaggerated claims and often an air of insolent superiority.”

Boasting and bragging have also been captured in a number of popular vernacular sayings, including, “tooting one’s own horn,” “patting oneself on the back,” and “singing one’s own praises.”

Before we delve more fully into the subject, there’s one other term you should know, and it’s directly related to our Mystery Woman’s earlier observation about artfully clothing one’s boasts in the language of humility. After she offered that advice in 2005, so many Social Media users began doing exactly as she suggested that a new word was coined to describe it: humblebrag.

Comedian and writer Harris Wittels unveiled the term in a 2010 Tweet, describing it as a modest or self-deprecating statement that actually reveals something people are proud of. It’s essentially a boast disguised as humility, and is generally employed to brag without seeming arrogant (as in “I can’t believe I got nominated for another award. I feel so unworthy!”).

By all accounts, the practice of self-praise has been commonplace since the earliest days of civilization. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, dating back to ancient Mesopotamia (circa 2100 B.C.), Gilgamesh, the king of the ancient kingdom of Uruk, frequently boasted about his physical strength, his heroic deeds, and his semi-divine lineage. Here are two examples:

“Who is the most glorious of heroes, the most eminent among men?”

“I am Gilgamesh, who has seen everything; I am he who has experienced all things.”

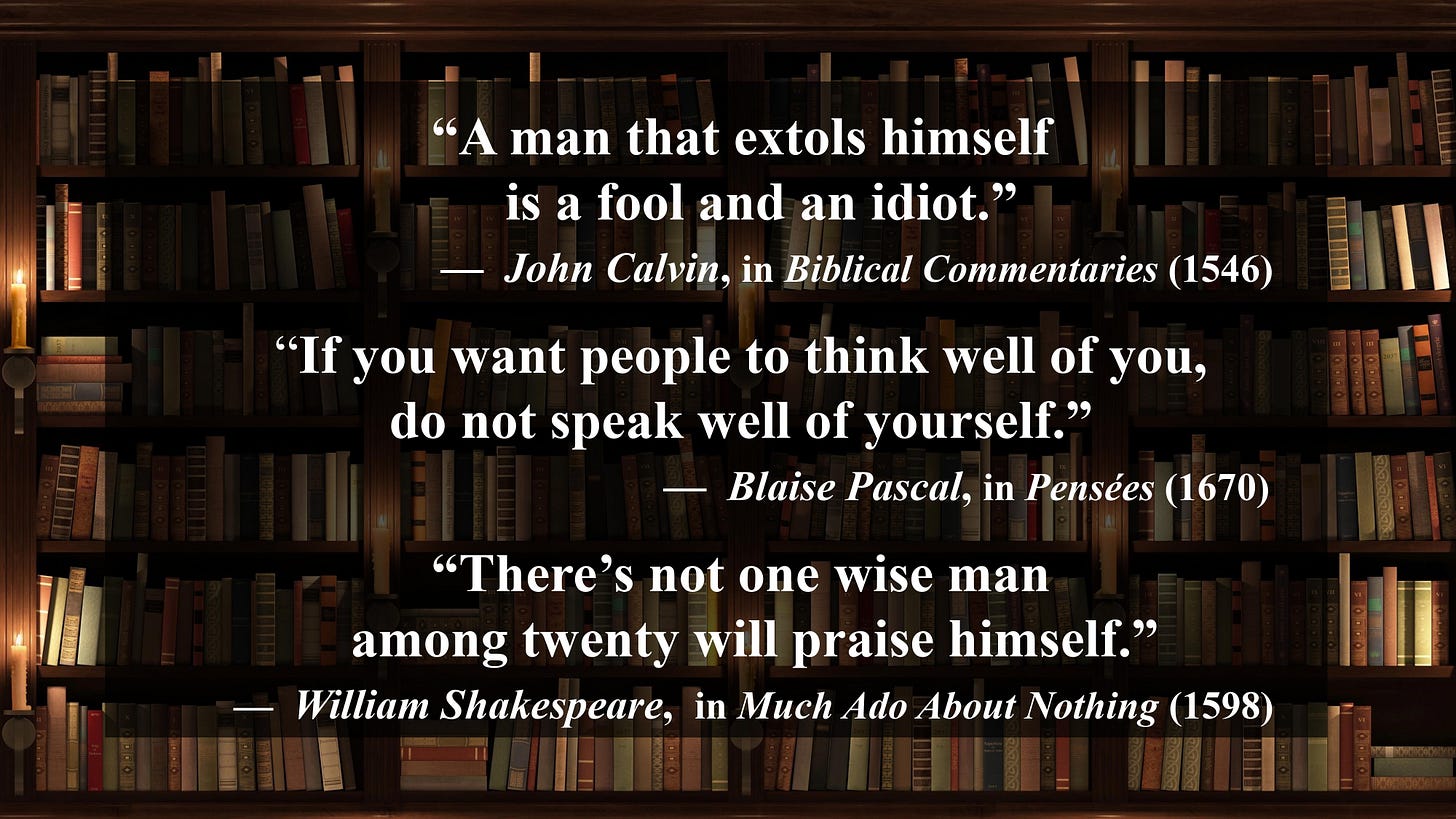

While the ruling class has boasted since ancient times, philosophers and religious leaders have consistently condemned the practice. You’ve already seen how Aristotle compared boasting to theft, and, while he had no way of knowing it, Lao-Tzu had already offered a similar observation in the Tao Te Ching (early 4th c. B.C.):

“He who exalts himself is not praised.”

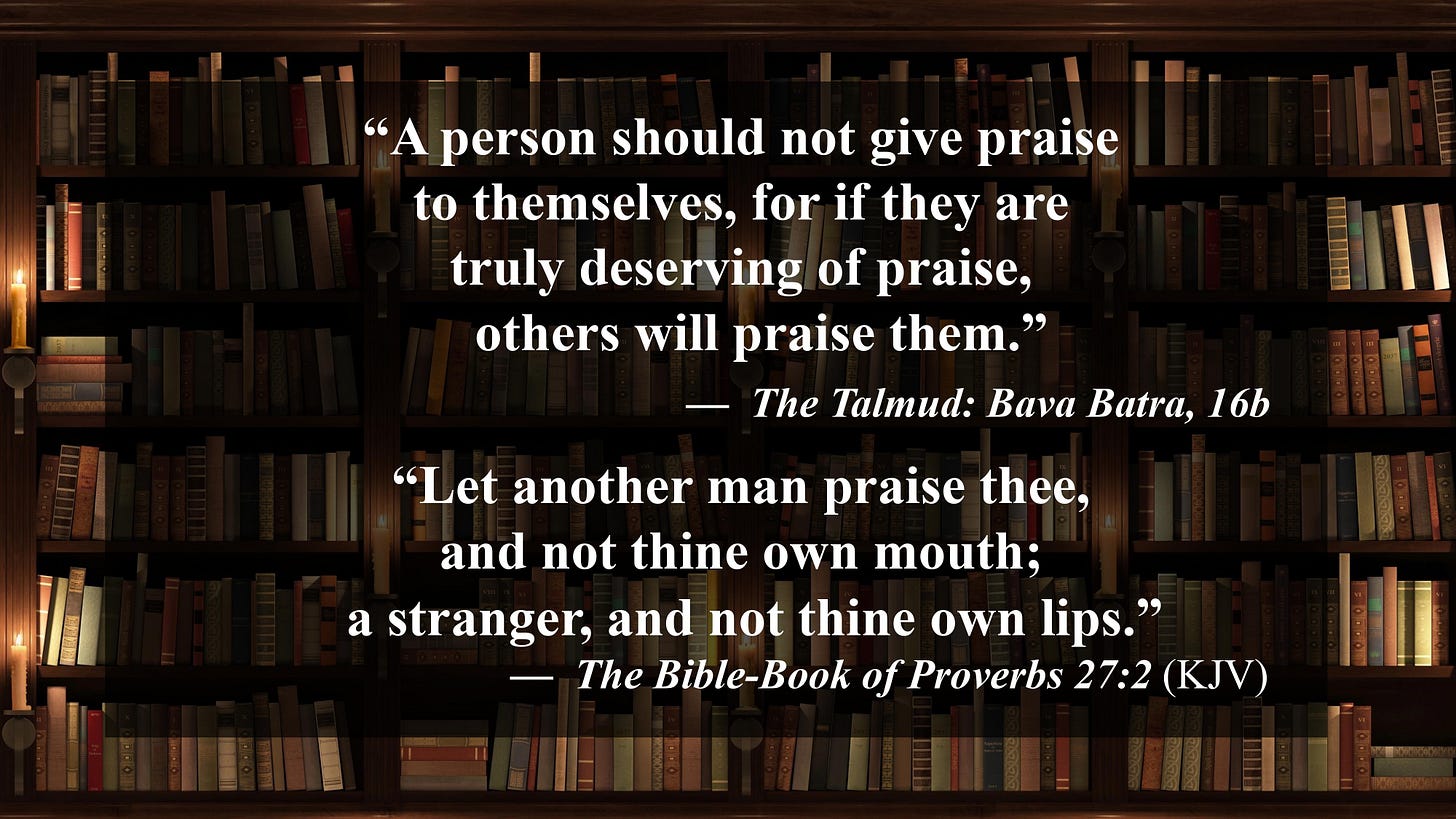

And, of course, virtually all members of the Jewish and Christian communities are familiar with these two observations:

Over the years, I’ve explored the issue of boasting many times with my devout Christian and Jewish friends, and it seems to me that they have viewed self-praise with disdain not simply because Scripture frowns upon it, but for two additional reasons. One, boasting and bragging are a categorical rejection of the virtue of humility; and two, both behaviors represent a complete surrender to the vice of pride.

Based on the writings of ancient philosophical thinkers and religious leaders—some of which we’ve sampled here—the predominant view of most people throughout history has been that boasting and bragging, while commonplace, are signs of boorishness, misguided thinking, or moral deficiency.

Over the last century and a half, however, the emergence of the field of psychology has significantly helped to expand our thinking about self-praise—and if I had to summarize the current state of thinking on the subject, it would go something like this.

Boasting is an emotionally immature attempt to elevate one’s status, quite commonly seen in children who have not yet developed a sufficient level of maturity or emotional intelligence. When it occurs among adults, it is not only a key indicator of stunted emotional growth, it also reflects a significant lack of awareness that boasting doesn’t impress people, it turns them off. Boasting stems mainly from feelings of inadequacy and poor self-esteem—and is best viewed as an attempt to mask personal insecurities and compensate for serious doubts about self-worth.

The specific subjects that people boast about are also key, for they generally pinpoint the exact areas where they feel most vulnerable. Boasting also has a distinctive “It’s all about me” quality that makes it indistinguishable from narcissism. In general, boasters are also highly sensitive to criticism, and, not surprisingly, they experience great difficulty in forming and sustaining intimate relationships. Most also show such little personal insight that their behavior becomes highly resistant to change. When chronic boasters become old, it is not uncommon for them to become socially isolated and angry, making them chronic complainers as well.

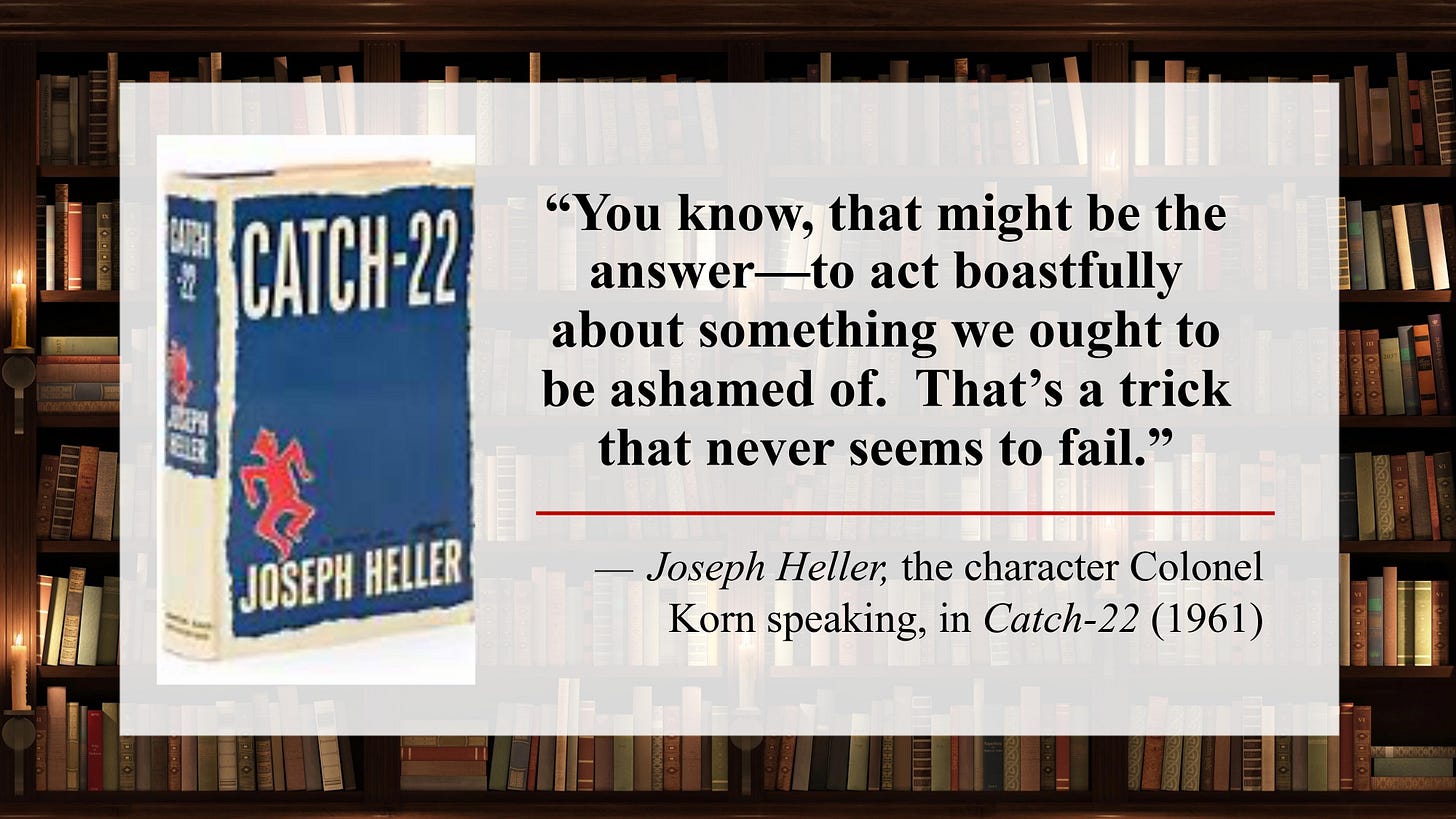

Let me bring my remarks to a close by mentioning a remarkable variation on the theme from Joseph Heller’s classic 1961 novel Catch-22. Set in WWII, there’s a scene in which two U.S. Army officers are having a conversation about what to do after a disastrous military mission has bombed an undefended Italian village—not once but twice.

Typically, a military blunder like this would lead to an officer’s dismissal or resignation in shame, but Colonel Cathcart—the man who ordered the mission—is looking for another option. As he discusses the whole matter with Colonel Korn, one of his buddies, the two men strategize about how they might preserve Cathcart’s reputation. As the conversation proceeds, an idea emerges: instead of admitting fault or showing regret, perhaps Cathcart should begin to simply boast about the mission as if it were a great success. Colonel Korn says about the idea:

Remember, Catch-22 is a satire, so this was Heller’s way of cynically suggesting that people are often far more impressed by a duplicitous display of bravado than an honest and honorable admission of failure.

I’ve always loved the foregoing passage from Heller’s book, but I wasn’t quite prepared for what happened as I was working on my newsletter this past week. In what can only be described as a spectacular coincidence, a candidate for the U.S. Presidency employed the precise strategy described in Catch-22—in this case boasting that the political liability known as “rambling” was in fact a brilliant form of discourse known as “the weave.” To see it for yourself, click the link below (and be prepared to endure a brief portion of a political advertisement before you can click the “skip” button):

Heller died twenty-five years ago—in 1999, at age 76—and while I can’t vouch for the accuracy of the reports, I’ve heard that, at the exact moment “the weave” was being announced, faint sounds of derisive laughter appeared to be emanating from the Green River Cemetery in the Long Island community of Springs, New York.

This week, think about how self-praise, bragging, and boasting have shown up in your life—whether you’ve engaged in the practice yourself or simply observed it in others. And as you approach the subject, let your thinking be stimulated by this week’s selection of quotations on the theme:

The less you speak of your greatness, the more I will think of it. — Francis Bacon

It’s a weak nation, like a weak person, that must behave with bluster and boasting and rashness and other signs of insecurity. — Jimmy Carter

If I do not praise myself, it is because, as is commonly said, self-praise depreciates. — Miguel de Cervantes

The praise you take, altho’ it be your due,/Will be suspected if it come from you. — Benjamin Franklin

He was like a cock who thought the sun had risen to hear him crow. — George Eliot

Nothing can be more true than that the greatest Boasters have the least of what they pretend to. — Eliza Haywood

Self-Praise is for losers. — John Madden

In private life there are few beings more obnoxious than the man who is always loudly boasting. — Theodore Roosevelt

You can boast about anything if it’s all you have. Maybe the less you have, the more you are required to boast. — John Steinbeck

Where boasting ends, there dignity begins. — Edward Young

For more quotations on the theme of SELF-PRAISE, go here. For quotations on BOASTING & BRAGGING, go here.

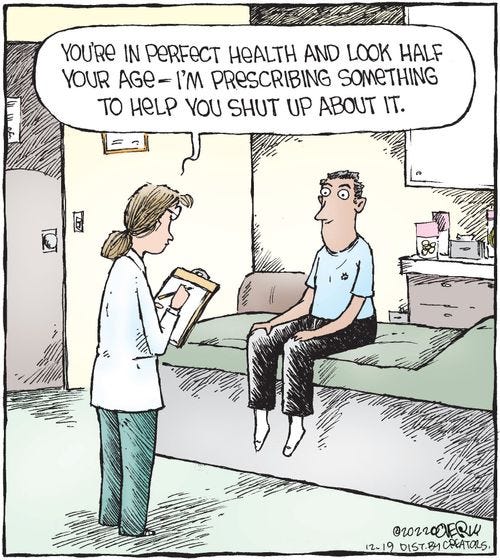

Cartoon of the Week:

Answer to This Week’s Puzzler:

Judith Martin, “Miss Manners”

Dr. Mardy’s Observation of the Week:

Thanks for joining me again this week. See you next Sunday morning, when the theme will be “The Surprises of Old Age.”

Mardy Grothe

Websites: www.drmardy.com and www.GreatOpeningLines.com

Regarding My Lifelong Love of Quotations: A Personal Note

The weave is not in his head; it is on it.

What Role Has “Self-Praise” Played in Your Life?

I hate to brag, but....