Dr. Mardy's Quotes of the Week ("Self-Inflicted Wounds")

September 22—28, 2024 | THIS WEEK'S THEME: “Self-Inflicted Wounds"

Opening Line of the Week

We all have fatal flaws, but what makes them so dangerous is that they’re almost always ignored, minimized, explained away, dismissed, or denied. To see someone readily admit to one, even in a novel, is unusual and refreshing.

The frank admission comes from January Andrews, a 29-year-old author of romance novels. After a taste of commercial success, Andrews is now broke and almost homeless. She continued on the subject of fatal flaws:

“I like to think we all do. Or at least that makes it easier for me when I’m writing—building my heroines and heroes up around this one self-sabotaging trait, hinging everything that happens to them on a specific characteristic: the thing they learned to do to protect themselves and can’t let go of, even when it stops serving them.”

In what went on to become an annual end-of-year post on Smerconish.com, I included Henry’s novel in my compilation of “The Twenty Best Opening Lines of 2020” (to be seen here).

For nearly 2,000 memorable opening lines from every genre of world literature, go to www.GreatOpeningLines.com.

This Week’s Puzzler

On September 28, 1891, this man died at age 72 in New York City. He is now considered one of America’s greatest novelists, but at his death he was regarded as a minor American writer who was best known for Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846). The book was an account of his experiences in the South Pacific after he jumped ship from a New England whaling vessel. Typee was successful enough to warrant an 1847 sequel: Omoo: A Narrative Adventure of Life in the South Seas.

These two books—the most successful in his lifetime—were followed by more than a dozen later works, none of which achieved commercial success or critical acclaim. At his death in 1891, all of his books were out of print and he was flirting with obscurity. His death was briefly mentioned in The New York Times, but the paper misspelled the title of the novel that is now indelibly associated with his name.

In 1917, critic Carl Van Doren wrote an article praising him. That article, combined with a 1919 centenary celebration, revived interest in the author. Six years later, in 1923, D. H. Lawrence also praised the man and his works, especially an 1851 adventure novel that is now regarded as one of America's greatest literary works.

In 2014, English critic Robert McCrum hailed the 1851 book as “the supreme American novel,” ranking it number 17 on his list of history’s 100 greatest novels. About it, he wrote: “It is a literary performance that is exhilarating, extraordinary, sometimes exasperating and, towards its apocalyptic climax, unputdownable.” And, parenthetically, the novel also began with one of literary history’s greatest opening lines.

In his works, this Week's Mystery Man offered memorable observations on countless topics, including this from his 1850 novel White-Jacket:

Who is this man? What is the title of the 1851 novel? What was the opening line? How was the title misspelled by The New York Times in 1891? (Answers below)

Have You Ever Suffered from a Self-Inflicted Wound?

The phrase self-inflicted wound can be employed literally or metaphorically—and there’s a world of difference between the two.

Literally, self-inflicted wounds are physical injuries that people cause to themselves. They can be accidental, as when people carrying a weapon stumble and incidentally shoot themselves, or purposeful, as when despairing people slit their wrists with a razor blade. With literal self-inflicted wounds, the most important thing to remember is that they always involve self-harm.

When speaking metaphorically about self-inflicted wounds, by contrast, we’re not generally referring to actual physical injuries, but rather to bad results, negative consequences, or unfortunate outcomes—like getting fired from a job, being “dumped” by a spouse or lover, losing one’s reputation, or being convicted of a crime.

In cases like these, the wounds are not “real,” but they’re still painful—often extremely so—and they all have one thing in common: they occurred in large part because the people suffering from them played a major role in making them happen. With metaphorical self-inflicted wounds, the thing to remember is that they always involve a form of self-sabotage.

If I were to attempt a dictionary-like definition, it might go something like this:

"Self-inflicted wounds are negative—and sometimes catastrophic—consequences that result from people acting or thinking in ways that are inimical to their own long-term best interests. The wounds, when they finally occur, often have their origin in actions, thought patterns, and choices that people may have originally regarded as benign or even useful, but ultimately became detrimental—and even hazardous—to their own physical, emotional, or interpersonal well-being.”

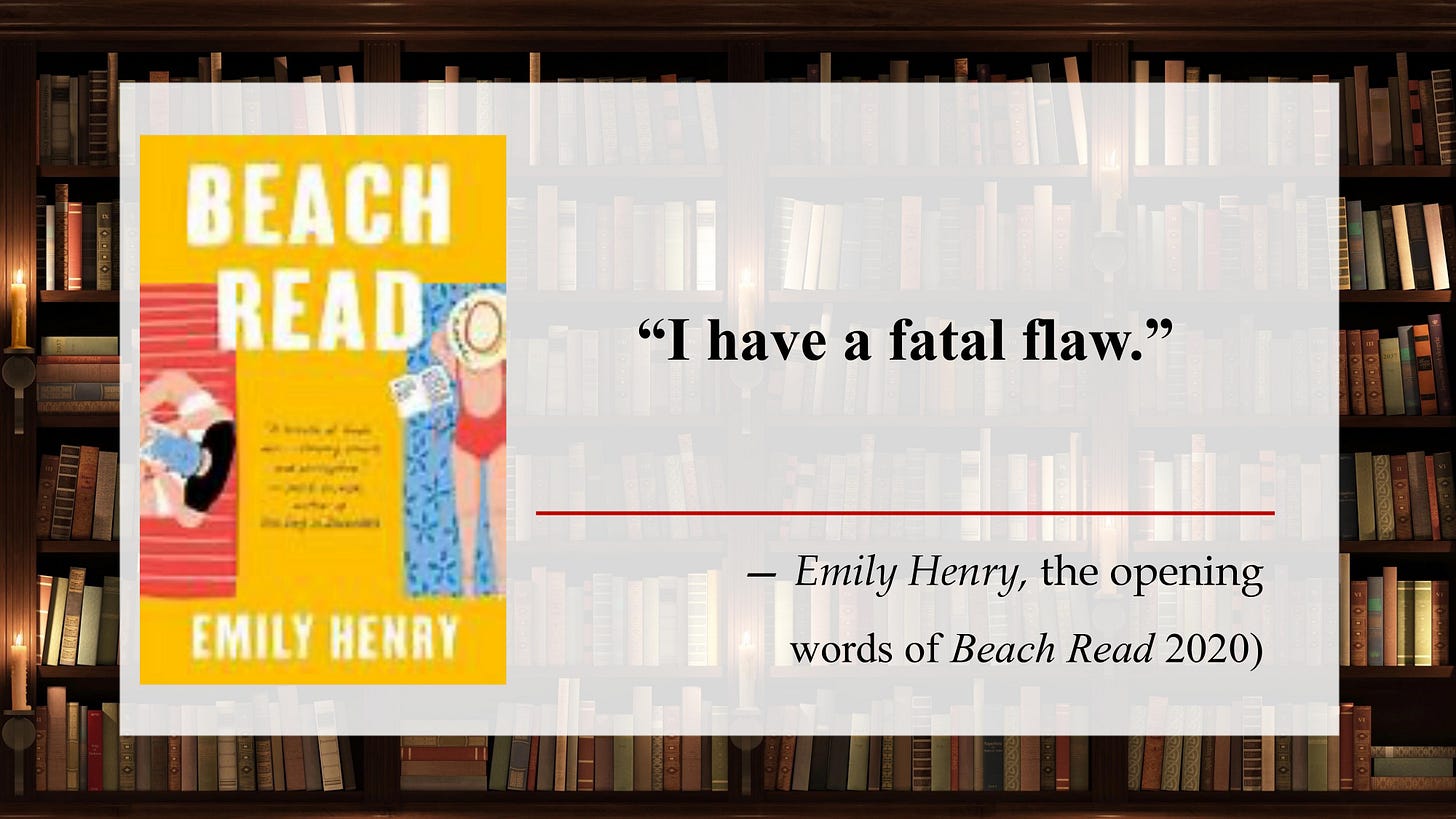

The quotation in this week’s Puzzler asserts that many of the evils that befall human beings are self-inflicted. While it doesn’t specify the nature or dynamics of the internal forces that are at work, it clearly suggests that people are essentially unaware of the contribution they’re making to the problems they’re experiencing. The basic idea goes back to antiquity.

When bad things happen, it’s easy—and for many, often quite tempting—to blame external factors: poor timing, bad luck, and, of course, other people. All of the observations above, though, suggest that unfortunate—and even tragic—events in life may often be traced to deep forces within the very people who are suffering from them.

Over the centuries, many popular sayings have emerged to describe the nature of self-sabotage, including “stabbing oneself in the back,” “shooting oneself in the foot,” “being one’s own worst enemy,” and, of course, “hoist with his own petard” (for an explanation, go here). All of these sayings vividly capture the nature of self-sabotage.

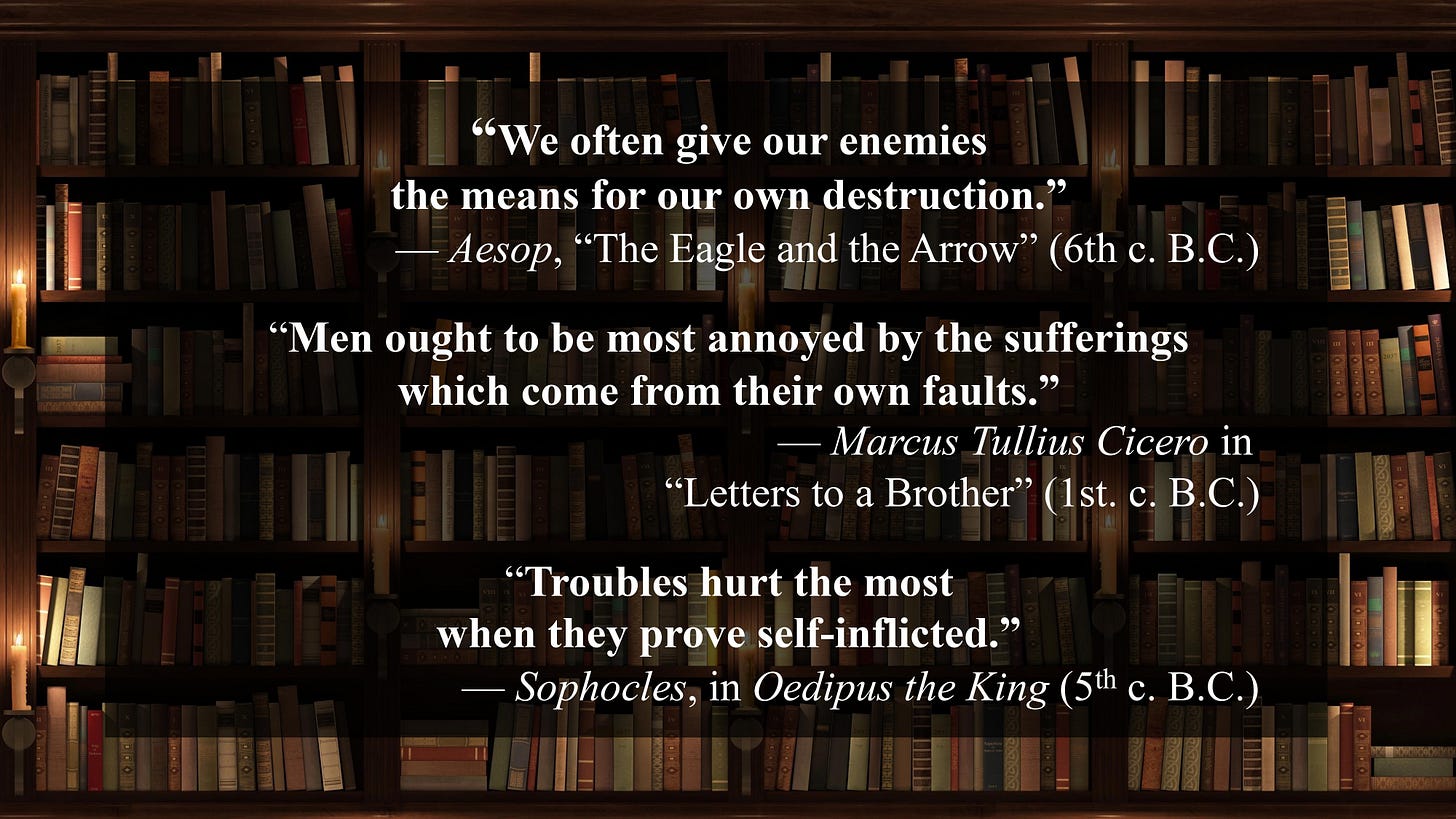

As you think about your own life, it’s quite possible you’ve been fortunate and have concluded, “So far, I’m happy to report that I haven’t really suffered any major self-inflicted wounds.” For the sake of argument, though, let’s say that, in recent years, you’ve found yourself becoming an angry, resentful, negative-thinking person who believes you’ve gotten a raw deal out of life. If that is true, you would be wise to heeds the words of one of our modern’s era’s most profound thinkers:

As this observation suggests, self-inflicted wounds tend to occur when a person’s world has been upended as a direct result of the ways in which they view themselves and the world in which they live. In his example, Tolle was thinking about angry and resentful people, but the point he’s making applies to anyone who’s engaging in irrational or misguided thinking, perceiving the world in unproductive or unhealthy ways, and making questionable or risky choices.

The tricky thing about self-inflicted wounds is that the vast majority of people don’t even think about them until after they’ve occurred. The implication is clear: the best approach is to recognize that the seeds of a devastating future consequence already exist in something you’re currently thinking, feeling, or doing. This makes right now the perfect time to begin charting a different course, one that will take you to a far more desirable destination.

I’ve been fortunate that no self-inflicted wounds have devastated my life, but if I’m being honest, I have to admit that a few “warning themes” have emerged. Some have to do with deeply ingrained lifestyle choices—especially around eating—and I’ll have more to say about this in a future post.

The one I will mention has also been around for quite some time, and is probably rooted in some long-standing and deep-seated insecurities I’ve never fully put to rest. The behavior in question occurs in social situations when I try to be clever and witty—and it backfires. So far, the failures have generally had more of a faux pas quality, but it’s certainly resulted in some soul-searching and self-recrimination on my part. Not surprisingly, there’s a quotation that captures my situation perfectly:

Up to this point, our focus has been on how self-inflicted wounds show up in the lives of individuals, but the problem also shows up in large groups, as the historian Barbara Tuchman suggested in her most famous work:

The March of Folly is one of my favorite books, and this is one my favorite opening lines. When I read the passage for the first time, my initial reaction was to think that her observation about governments applied equally well to individuals—and therefore an important contribution to this week’s theme.

In her opening paragraph, Tuchman continued: “Mankind, it seems, makes a poorer performance of government than of almost any other human activity.” In many ways, though, when it comes to the way we human beings have treated the planet we live on, her observation could easily be extended to the entire human species.

In many respects, that’s exactly what the legendary cartoonist Walt Kelly did in a 1970 Pogo cartoon strip:

And, as many of you know, that same year, Kelly took the same message and used it in a now-legendary poster that was used to commemorate the very first celebration of “Earth Day.”

Even though we’ve been discussing a serious subject this week, it is not without its humorous aspects. In 2008, the respected New York Times columnist Thomas L. Friedman interviewed Bill Clinton on the subject of golf. The former president said a number of interesting things that day, but the one that really jumped out at me was when he said:

I’m a big fan of irony, and one of my favorite experiences is seeing people say things about any topic without sensing the irony in their remarks. Clinton offered the remark exactly ten years after the Monica Lewinsky scandal, widely regarded as one of the most egregious self-inflicted wounds in the history of the U. S. presidency.

For younger subscribers who may not recall the precise details, in televised remarks on January 26, 1998, the 51-year-old president denied having an extra-marital affair with a 24-year-old White House intern—ending his remarks by saying, “I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Ms. Lewinsky.” Further investigation, however, confirmed a several-year affair, and it all resulted in charges of perjury and his impeachment by the House of Representatives. After a 21-day trial in the U.S. Senate, Clinton was acquitted on all charges, but the whole matter will forever tarnish his legacy.

Every now and then, it’s a good idea to step back and think about ways we might be contributing to our own problems and, in effect, becoming our own worst enemies. As you reflect on all of this in your own life, let your thinking be stimulated by this week’s compilation of quotations:

Yet is every man his own greatest enemy, and as it were his own executioner. — Sir Thomas Browne

All honor’s wounds are self-inflicted. — Andrew Carnegie

Our greatest foes, and whom we must chiefly combat, are within. — Miguel de Cervantes

It’s a sad time when you find out that it’s not accident or time or fortune but just yourself that kept things from you. — Lillian Hellman

Men are not punished for their sins, but by them. — Elbert Hubbard

The hell to be endured hereafter, of which theology tells, is no worse than the hell we make for ourselves in this world by habitually fashioning our characters in the wrong way. — William James

We end self-sabotage only by taking responsibility for the choices and actions that created it. — Dan Millman

Self-destructive patterns cause as much suffering as outer catastrophes. — Anaïs Nin

In middle age we are apt to reach the horrifying conclusion that all sorrow, all pain, all passionate regret and loss and bitter disillusionment are self-made. — Kathleen Thompson Norris

Misfortunes one can endure—they come from outside, they are accidents. But to suffer for one’s own faults—ah! There is the sting of life. — Oscar Wilde

For source information on these quotations, and more quotations on SELF-INFLICTED WOUNDS, go here. For quotations on SELF-SABOTAGE, go here

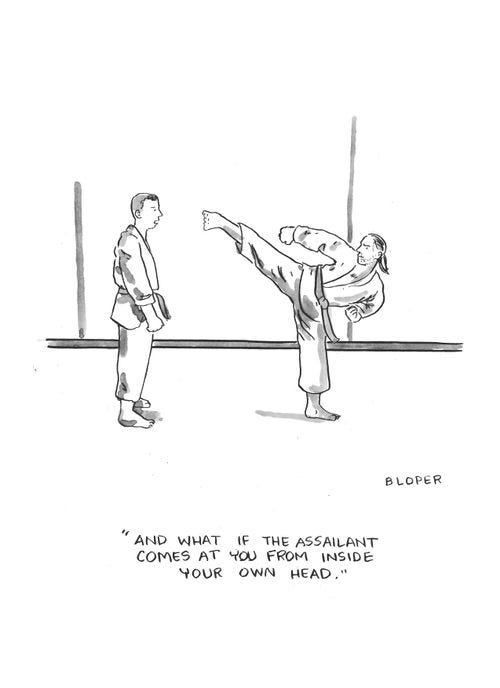

Cartoon of the Week:

Answer to This Week’s Puzzler:

Herman Melville. Moby Dick. “Call me Ishmael.” In 1891, The New York Times mistakenly spelled it Mobie Dick.

Dr. Mardy’s Observation of the Week:

Thanks for joining me again this week. See you next Sunday morning, when the theme will be: “Acts of Daring.”

Mardy Grothe

Websites: www.drmardy.com and www.GreatOpeningLines.com

Regarding My Lifelong Love of Quotations: A Personal Note

A lot to think about here for sure! But I think the best part is the cartoon! It is so true and made me laugh out loud!! Thank you!!!

Another great article, Mardy. I loved it. Beginning in college, I have tried to read Moby Dick and have never been able to finish it. Must be my fatal flaw.