Dr. Mardy's Quotes of the Week ("Credos & Creeds")

July 6 - 12, 2025 | THIS WEEK'S THEME: “Credos & Creeds"

Happy Independence Day!

Yet another Independence Day has come and gone, and I hope you were able to celebrate in style as well as remember why the day is so important. To finish off the holiday in proper fashion, I’m pleased to present below a brief (less than five minutes) exposition on the nature and significance of the day by the acclaimed historian Heather Cox Richardson. She has a special ability to bring history to life, and I think you’ll agree that she does that very nicely here. Simply click the link below:

Opening Line of the Week

These are the opening words to the book’s Preface. In the first paragraph, Coffin continued:

“However imperfectly, I have given my heart to the teaching and example of Christ, which, among many other things, informs my understanding of faiths other than Christianity.”

I’m currently working on “The Best Opening Lines of 2025,” and if you’d like to nominate any candidates, e-mail them to me at: drmardy@drmardy.com. If you recommend a great opener I haven’t yet seen and it makes my final list, I’ll send you a personally-inscribed copy of one of my books.

This Week’s Puzzler

On July 13, 1903, this man was born into a wealthy London family (his father had inherited a fortune from his Scottish ancestors and went on to achieve notoriety as “the man who broke the bank at Monte Carlo”). Raised in an atmosphere of privilege and educated at England’s best schools, he developed an early passion for art and carried this passion with him until his death at age 79 in 1983.

He was a teenager at Winchester College—one of England’s oldest and most prestigious boarding schools for boys—when he became enthralled with the world of art, an interest that was fueled by the writings of the noted English art critic John Ruskin. At age nineteen, he went on to Trinity College, Oxford, where he formally majored in modern history but devoted most of his attention to the study of art.

He was only twenty-five when he wrote his first book—The Gothic Revival—in 1928. In the 1930s and 40s, he served as Director of Britain’s National Gallery. During WWII, he became a national hero for protecting artworks from bombing raids, keeping the museum open to the public, and hosting free lunchtime and evening concerts.

He will be forever remembered, though, as the writer, producer, and host of BBC-TV’s Civilisation, one of broadcast history’s most successful and influential documentary television series (first broadcast in England in 1969, and the following year in America on PBS).

The series introduced the world of art to millions around the world. It also spawned a beautifully illustrated book by the same title that became a huge bestseller (it still occupies an honored place in my personal library). A 1983 Time magazine article said of the series:

“If it had not been for Civilisation, none of the didactic series that came after it, starting with Jacob Bronowski’s Ascent of Man and Alistair Cooke’s America, would have been made.”

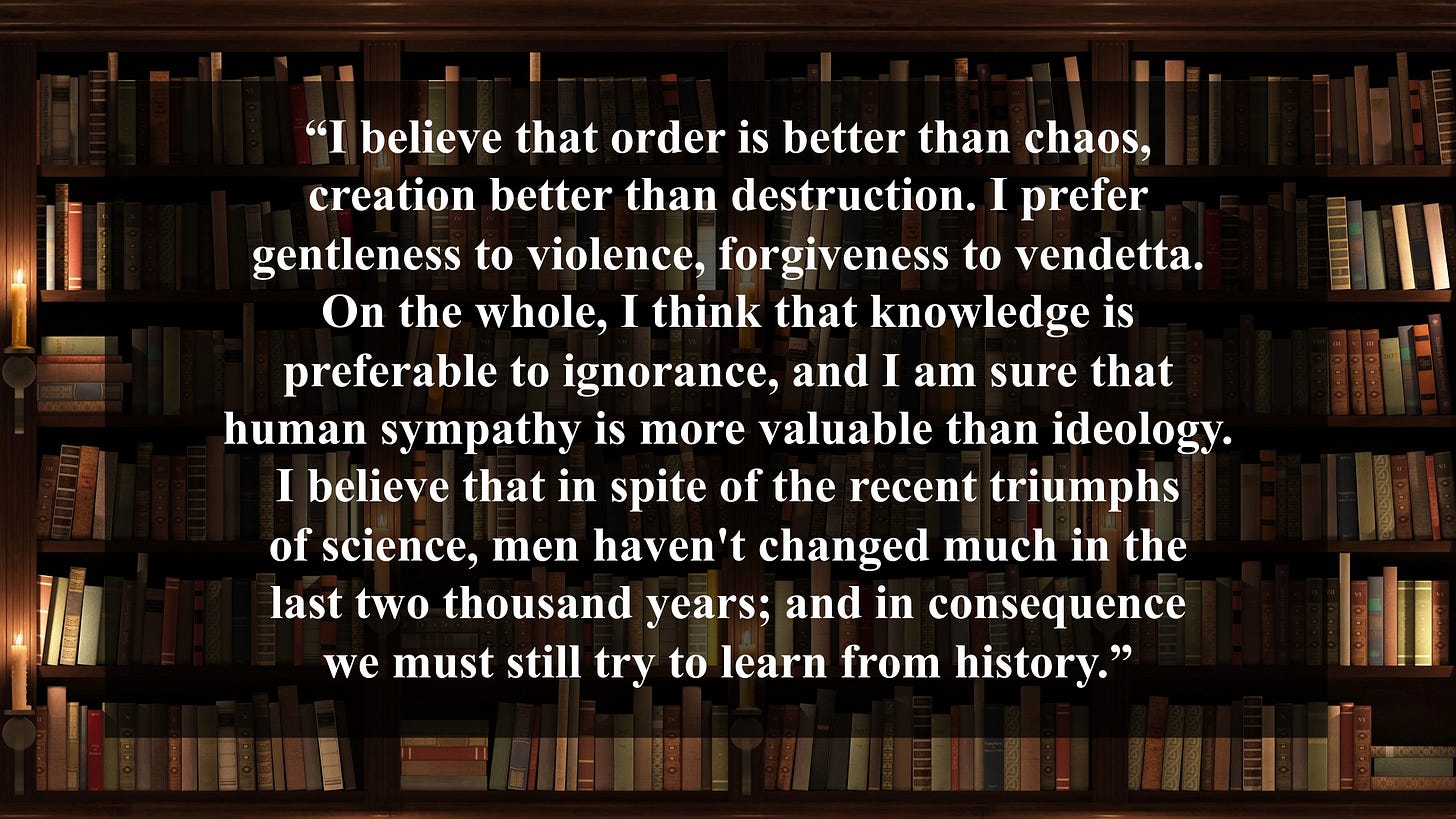

Near the end of the companion book Civilisation (1969) this week’s Mystery Man took a step back and offered a compelling summary of his beliefs:

Who is this person? (Answer below)

Do You Have a Personal Creed or Credo?

In modern English, the word credo—in Latin, it literally means “I believe”—refers to a succinct summary of one’s core beliefs and guiding principles. While the word is properly pronounced KREE-doh, the non-standard pronunciation KRAY-doh is growing in popularity in informal speech.

Creed is the English word for credo and for many centuries has referred to a formal statement of the beliefs one must hold to be considered, say, a Christian. We see that in The Apostles' Creed, which, appropriately, begins with the words “I believe” and goes on to enumerate twelve tenets of the faith (the prayer is called the “Apostles’” creed because each one of the twelve apostles was said to have contributed an article of faith). The prayer fits perfectly into Wikipedia’s definition of a creed:

“A creed…is a statement of the shared beliefs of a community (often a religious community) which summarizes its core tenets.”

Over the centuries, religious history was filled with so many conflicts over rigidly-applied creeds that the word itself took on a negative connotation. I won’t go into the details here, but the stature of the word fell so low by the mid-1800s that Ralph Waldo Emerson described a creed as “a disease of the intellect” in his 1841 “Self-Reliance” issue. In an 1896 poem, Ella Wheeler Wilcox also took an indirect swipe at the word when she wrote:

Over time, though, the publication of so many eloquent creed statements from secular writers gradually helped to re-establish the term’s reputation, and by the early 20th century, creed—and the companion term credo—were being used to describe any formal statement of a person’s core beliefs and guiding principles. The passage in this week’s Puzzler is a perfect example, and could be accurately described by either term, creed or credo.

Sometimes, a formal creed or credo statement doesn’t capture all that an author wanted to say, and that was the case with this week’s Mystery Man, who went on to add:

I’ve been collecting credo and creed statements for many years, and have come to regard them as a kind of declaration of self. In many ways, they are analogous to what the Founding Fathers did in the Declaration of Independence in 1776. By using the words “we hold these truths to be self-evident,” they were clearly entering the philosophical as well as the political domain. The whole matter was beautifully captured by G. K. Chesterton, when he wrote in What I Saw in America (1923):

“America is the only nation in the world that is founded on a creed. That creed is set forth with dogmatic and even theological lucidity in the Declaration of Independence; perhaps the only piece of practical politics that is also theoretical politics and also great literature.”

Even though Ella Wheeler Wilcox might have said, “My credo is kindness,” most creed and credo statements don’t restrict themselves to a single belief, like I believe in God, or a single idea, like the unexamined life is not worth living. By far, the most common pattern is a series of concise and carefully considered beliefs and principles that, taken together, form not exactly a philosophy of life so much as a philosophy of living.

Credos and creed statements can also get a bit wordy, which is to be expected when people are describing their core beliefs and guiding principles. And when well written, they can have a soaring majesty, as we see in this 1920 effort by D. H. Lawrence:

It is not essential for a personal declaration to use the phrase “I believe” or explicitly label itself as a creed or credo. If it expresses the core convictions that guide a person’s life—what they value, how they wish to live, and what they stand for—that’s all that is required. We see all of that—and more—in a set of remarks Jack London made to a group of friends who visited his California ranch in November of 1916:

In my experience, something special happens when you read the credo of an author you’ve long admired. It’s like crossing a threshold into an inner sanctum, or a private study that’s rarely open to the public. In this special—almost sacred— space, you’re no longer a fan. You’re more like a confidant, or fellow-traveler, who’s gaining a deeper appreciation of someone you thought you already knew quite well.

Personal credo statements became part of American culture in the 1950s with CBS-Radio’s “This I Believe,” a five-minute radio program hosted by Edward R. Murrow. Over four seasons, Murrow asked famous Americans—including Helen Keller, Jackie Robinson, Harry Truman, William Faulkner, Pearl Buck, and James Michener—as well as everyday people to write short essays about their beliefs, values, and guiding principles—and then read them on the air. Many of the 800 essays were collected in later published books—all with This I Believe titles—and I devoured them as a young man. They included such gems as the following from a 1953 essay by the American financier Bernard Baruch:

Over the years, a variety of revivals of Murrow’s “This I Believe” format have been hosted on National Public Radio and Public Radio International. The current “This I Believe” website contains all of the nearly 800 essays—many with voice recordings—from the Murrow years as well as over 125,000 essays that have appeared since. Despite the glorious content, though, you should know that the site is not particularly user-friendly. You can judge for yourself by going here.

The world of literature is filled with examples of creeds and credos, but they occasionally show up in other places as well. The most famous example that comes to mind is Frankie Laine’s 1953 hit song, “I Believe”:

So, What About You?

Let me bring my remarks to a close this week by repeating the words I began with: Do you have a personal creed or credo? If not, it’s something you might want to consider.

In the future, I plan to devote an entire post to “Crafting Your Credo,” but for now, just let me say that writing a credo or personal creed statement is an unrivaled values clarification exercise. Compared to writing your own epitaph, mission statement, or personal mantra, writing a credo is in a league of its own. To get started, you might want to stimulate your thinking by perusing the many specific examples I’ve included in my DMDMQ.

When you’re ready to embark on the exercise, remember that a credo is declarative, not performative. It’s something you’re writing for yourself, not for an audience. It’s not like a resume, in which you’re trying to impress others or “sell” yourself. And remember, it’s not simply a personal declaration of your core values and deeply held beliefs, it’s a document that reveals who you truly are.

I composed my first credo statement many decades ago, and I occasionally go back to “tweak” certain elements. Based on the idea that a credo is personal document rather than a public performance, I’ve shared mine in personal conversations, but have no plans to ever publish it. I’m glad other people have “gone public” with theirs, though, because their efforts have helped clarify and sharpen my thinking. And so have these other observations on this week’s subject:

My creed is simple: All life is sacred, life loves life, and we are capable of improving our behavior toward one another. — Diane Ackerman,

For the poet the credo or doctrine is not the point of arrival but is, on the contrary, the point of departure for the metaphysical journey. — Joseph Brodsky

A little humor can make life worth living. That has always been my credo. — Bennett Cerf

The most effective way I know to begin with the end in mind is to develop a personal mission statement or philosophy or creed. It focused on what you want to be (character) and to do (contributions and achievements) and on the values or principles upon which being and doing are based. — Stephen Covey

This became a credo of mine: Attempt the impossible in order to improve your work. — Bette Davis

The Narcissist’s Creed: I am, therefore you’re not. — Jim DeKornfeld

Thinking from the end causes me to behave as if all that I’d like to create is already here. My credo is: Imagine myself to be and I shall be, and it’s an image that I keep with me at all times. — Wayne W. Dyer

If I were asked to define the Hindu creed, I should simply say: Search after truth through non-violent means. — Mohandas K. Gandhi,

Economy is the first and great article…in my financial creed. — William E. Gladstone

Perhaps the single most important therapeutic credo that I have is that the unexamined life is not worth living. — Irvin D. Yalom

Cartoon of the Week:

Answer to This Week’s Puzzler

Kenneth Clark (1903-83)

Dr. Mardy’s Observation of the Week

Thanks for joining me again this week. See you next Sunday morning, when the theme will be “Discontent.”

Mardy Grothe

My Two Websites: www.drmardy.com and www.GreatOpeningLines.com

Regarding My Lifelong Love of Quotations: A Personal Note

The true story of Henry Yazi and God.

By Brent Scott

July 12, 2011

On my way to Prescott Valley today to do laundry, as I was in Dewey, I saw an old man walking along the road. I could see that he was a bit ragged and it was hot so I decided to ask him if I could give him a lift.

His name was Henry Yazi, a Navajo. It was hard to understand his words as he had a heavy native accent, few teeth, and was working a wad of gum that kept making an appearance between is lower teeth and is lower lip.

He said he had an appointment at the V.A. tomorrow. He started out in Flagstaff this morning. His niece dropped him off there. I was his fifth ride of the day. He was in the Army, in Viet Nam and Germany 1964, 1965, and 1966.

I asked him what his childhood was like. He said it was hard. His father finally was able to arrange for him to go to school but he said his English was poor and it made school very hard.

I decided to take him to where ever he needed to go. I wasn’t in a hurry and it was so easy for me to just sit there and drive. I asked him if he had a place to stay in Prescott and he said he would stay at the Mission. I assumed that that was a shelter provided by the Salvation Army. As we got into Prescott, he directed me away from down town and toward the medical center. He said that there was an Albertson grocery store where he knew someone who he could stay with. I dropped him off at the store. We shock hands. He said God bless you. I said it was a pleasure to meet him.

Driving back, I prayed. I don’t usually pray solicitous prayers. But I thought that this guy could really use some help, and that God ought to know about it. I prayed, “God if ever a person needed some help right now, Henry Yazi could use some. So, please send him some help.” Immediately the words came into my head “I just did.”.

There are resume traits and achievements, and there are eulogy traits and achievements. Your great grandchildren won't know much about you. For nearly all of us, hundred years after our deaths, we will be gone from memory. This is it. Right now. Try to be kind, now. That is a creed. As Elvis said, "Don't be cruel."