Dr. Mardy's Quotes of the Week ("Libraries")

August 18—24, 2024 | THIS WEEK'S THEME: “Libraries"

Opening Line of the Week

This understated-but-evocative opening line pulled me right in. It comes from an unnamed, middle-aged, female librarian who is surveying the patrons moving here and there in the large main room of her library. In only ten words, she nicely established the setting and immediately got me thinking about what “kind” of person was going to be featured in her story. The entire opening worked so well that I felt a sense of heightened anticipation when she finally introduced the novel’s protagonist:

“Rannee is different. She belongs to no group. She travels alone. She is a handsome young black woman with smooth skin and soft features and a ‘calm so deep’ I used to think of her as Serena. She has been coming for years. Now, of course, she comes every day. She treats the library more like a church than a depot. She walks silently between the shelves like pews and slides the books gently from their niches. She is reading her way through Fiction. History, she tells me, will be next. It is her history that interests me.”

For nearly 2,000 memorable opening lines from every genre of world literature, go to www.GreatOpeningLines.com.

This Week’s Puzzler

On August 22, 1920, this man was born in Waukegan, Illinois. Raised in a blue-collar family, he was an intellectually curious child who preferred reading to playground games with friends. When he began elementary school, he was drawn to science fiction and fantasy tales featuring heroic figures like Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon.

Within a few years, he moved on to masters of the genre—including H. G. Wells, Jules Verne, and Edgar Allen Poe. By age eleven, he began writing his own short stories, and at age twelve, he embarked on his first serious writing effort, an attempt to write a sequel to an Edgar Rice Burroughs novel.

At age fourteen, he and his family moved to California. While attending Los Angeles High School, he became a huge movie fan, but also deepened and expanded his sci-fi interests. He graduated from high school in 1938. Decades later, he wrote about that period of his life:

After publishing his first story in 1938—at age 18—he spent nearly a decade trying to make it as a writer (severe vision problems kept him out of military service in WWII). While some stories were published in pulp fiction magazines (“the pulps”), he had no success in getting into “the glossies.”

In 1946, he entered a short story (“Homecoming”) in a Mademoiselle magazine competition. The story was about a young boy who, lacking supernatural powers himself, felt like a complete outsider at a family reunion of witches, vampires, and werewolves. The tale resonated with a young staffer named Truman Capote, who plucked it from a slush pile of submissions. After it was published, it went on to become one of the year’s best American short stories.

Over the next several decades, he became one of literary history’s most popular and influential writers. Some of his science-fiction stories have become classics, notably The Martian Chronicles (1950), The Illustrated Man (1951), Fahrenheit 451 (1953), and Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962).

This week’s Mystery Man often paid tribute to the role libraries played in his life, but never better than in these two observations:

Who is this person? (Answer below)

How Important Have Libraries Been to You?

The American Heritage Dictionary defines library as: “A place in which reading materials, such as books, periodicals, and newspapers, and often other materials such as musical and video recordings, are kept for use or lending.”

As often happens with dictionary definitions, this one is thorough and complete, but it is also sterile and lifeless—so it’s probably better to begin our discussion of libraries with something that more memorably captures the essence of the subject.

Etymologically, the word library can be traced to the Latin liber, which originally meant “the inner bark of trees” and ultimately evolved to mean “book, paper, parchment.” The etymology also provides an important hint about how long libraries have been around.

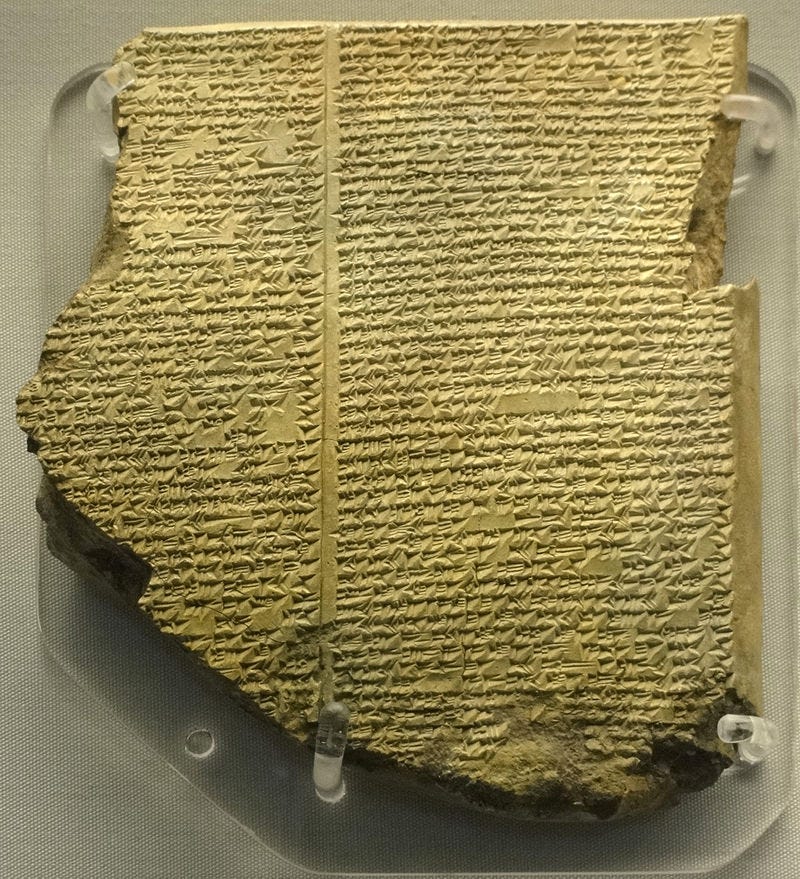

History’s first library was constructed in modern-day Iraq in the 7th century B.C. Named after the last king of the Assyrian Empire, The Library of Ashurbanipal was a magnificent structure that housed a vast collection of cuneiform (clay) tablets on a wide range of topics, including religion, science, literature, and law. The library was much more than a collection of tablets, though. It was a center for study and scholarship, reflecting the ruler’s desire to celebrate human achievement. The most famous tablet in the collection was the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of history’s first great literary masterpieces.

As a writing surface, however, clay left a lot to be desired. The same was true of tree bark, which was the preferred method a few thousand miles to the east in ancient India. Given human ingenuity, though, it was only a matter of time before more effective methods would emerge—and that is exactly what happened with papyrus and parchment.

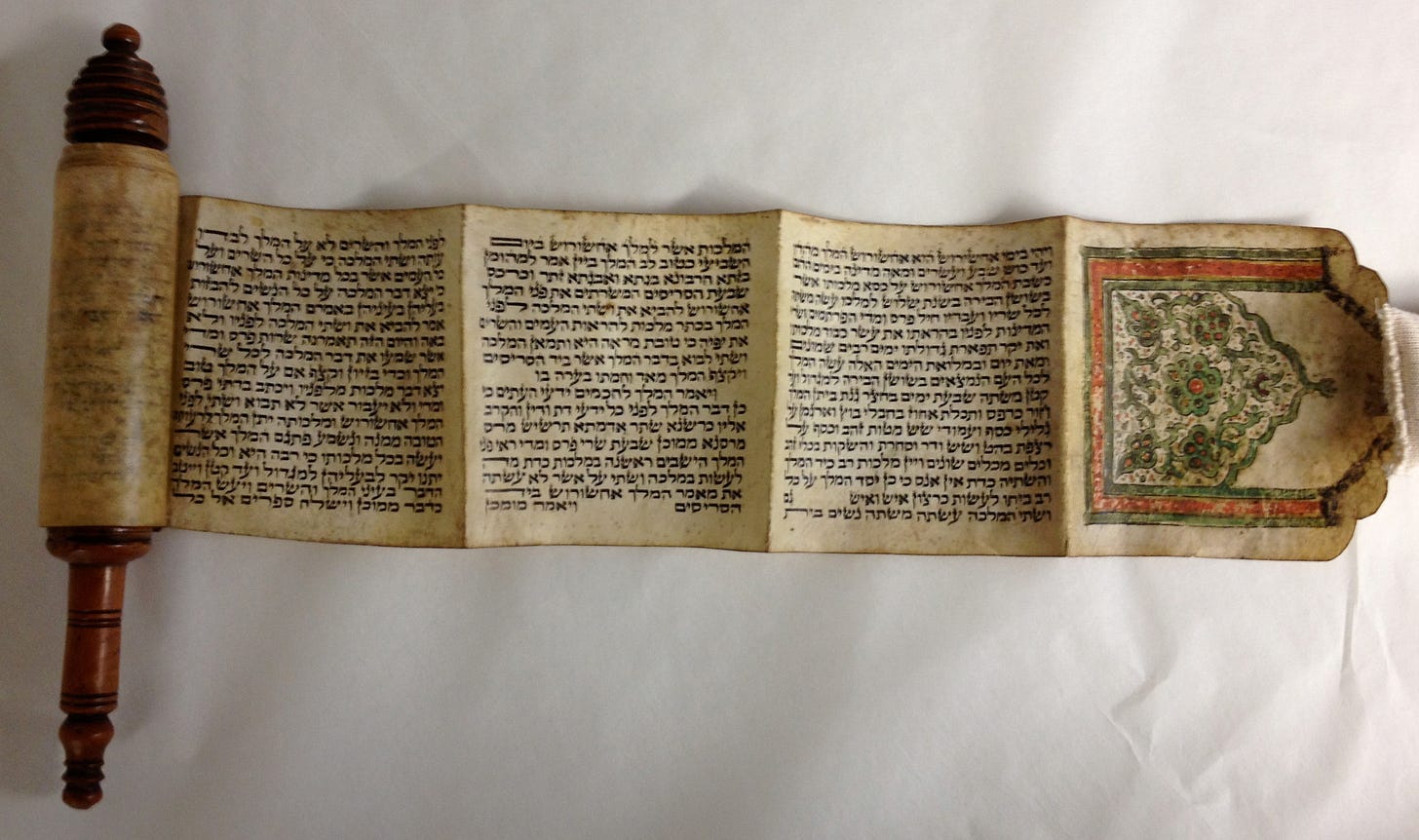

Papyrus scrolls, first used in ancient Egypt, were made from the pith of papyrus, a flowering plant found in abundance in the Nile Valley. And parchment scrolls, favored in ancient Greece, were made from specially prepared skins of animals, primarily sheep, calves, and goats. When properly prepared, both papyrus and parchment resembled a thick sheet of paper—and when the individual sheets were joined together and rolled up into a scroll, they resembled the pages of a book.

I don’t want to belabor the issue of writing surfaces, but it helps lay the groundwork for any discussion of libraries. Just think about it for a moment. For humans to develop as a species, two major developments were necessary. First, they needed to invent a way to take transient human speech and record it on a writing surface in some kind of permanent way. Second, as the number of these new “documents” began to mushroom, a new kind of institution would be needed to house, organize, and make them readily available to others. Without this new institution—now called a library—the great advances of human civilization would never have occurred.

As important as libraries have been to human civilization, they’ve been equally influential in the lives of countless numbers of young boys and girls. We saw that earlier with this week’s Mystery Man, and it was also true for me.

While my mother never went beyond the eighth grade, she was a voracious reader. From a very early age, I remember feeling deeply curious when she became so captivated by a book that she seemed to be off in a different place. To my young mind, it seemed like a book had a special power to enthrall people. I never saw it happen with my dad, or most of my other relatives, but by the time I started elementary school, I began to experience the phenomenon for myself. By the time I reached the third grade, I was hardly ever seen without a book close at hand.

There was no library in my small North Dakota hometown, so I was one very happy fourth-grader when we learned that a county “Bookmobile” would soon be making bi-monthly (twice a month) visits. That’s when, just like this week’s Mystery Man, I too became a child of the libraries.

I'll never forget the moment I first spotted the shiny new bookmobile parked at the end of Main Street. As soon as I stepped inside, the sight of all those books crammed into every nook and cranny took my breath away. For the next four years, my mom and I showed up for almost every bookmobile visit, returning the books from two weeks earlier and checking out new ones. It was like Christmas every two weeks, and no matter how expensive the books might have been in stores, they were completely “free” for me.

Within a few years, I became intimately familiar with the Dewey Decimal System. And during my seventh and eighth grades—my last two years at St. Nicholas Elementary School—I had the honor of being named “Assistant Librarian” in our small school library. My duties mainly included the checking out and re-shelving of books, but it also gave me a “pass” from the regular classroom for the last two periods of every school day.

Ever since, I love it when I learn that other people I respect and admire are also “children of libraries.” A few years ago, for example, I was delighted when I learned that Rita Mae Brown had said something along the lines of:

“When I got my library card, that was when my life began.”

And almost a decade ago, I got a similar warm feeling in my heart when Jeff Jacoby, the respected Boston Globe columnist (and someone I’m also proud to call a friend) wrote in a 2015 column:

This week, spend some time thinking about the question I posed earlier: “How Important Have Libraries Been to You?” But going forward, perhaps a more important question is, “How Important Will You Be to Libraries?” In a 2013 lecture at the Reading Agency, the British writer Neil Gaiman wrote:

“Libraries really are the gates to the future. So it’s unfortunate that around the world we observe local authorities seizing the opportunity to close libraries as an easy way to save money, without realizing that they are quite literally stealing from the future to pay for today. They’re closing gates that should be open.”

So this week, let me bring my remarks to a close with ten easy ways you can support your local library.

If you don’t currently have a library card, get one. Library membership drives usage statistics, which, in turn, increases the odds of getting adequate funding.

Check out library materials—lots of them. This may seem obvious, but when library officials attempt to justify their existence to local politicians, they rely heavily on circulation statistics.

Visit your library’s website—frequently. High traffic is an indication of community engagement and an important metric in funding and support decisions. Home pages provide: (a) information about upcoming programs: (b) links to a wide range of online resources; (c) access to local government and social service agencies, educational institutions, and other community organizations; (d) information about job openings and volunteer opportunities; and, finally, (e) an avenue for making suggestions or providing feedback.

Attend library programs and events. High levels of community engagement suggest a library that is a vibrant community resource—and more likely to be generously funded by our tax dollars.

Join the local Friends of the Library group. You won’t regret it. Several decades ago, I experienced one of the highlights of my “volunteer” life when I served as the President of the Friends of the Library in Bedford, Massachusetts.

Donate books if your library sells used books as a fund-raising tool.

Occasionally ask your library director or reference librarian, “How can I help?” A few years ago, in a conversation with local library director, she said she was trying to figure out which books to order in the new year. This was always a challenge, she added, because a limited budget meant she could not acquire all the books on her “wish list.” When I asked for an example, she said she would probably not be ordering the recently published Bartlett's Familiar Black Quotations.

The very next week, I saw the book in my local bookstore, purchased a copy—which, of course, was a good way to support my local independent bookstore—and then donated it to the library. When I saw the book on the library shelves a few weeks later, I opened it to discover a lovely note inside the front cover saying it was a gift to the library from me. It was a complete surprise—and a completely delightful one at that. Since then, I’ve made this a regular practice. I’d highly recommend it to you as well.

Whenever your can, compliment the library staff or express your appreciation to them in a heartfelt way. Mark Twain once said, “I can live for two months on a good compliment,” and I believe librarians may appreciate a kind word even more than him.

Use social media to promote your library. Even technically-challenged people like me know that “following” your library and sharing their posts on various social media platforms can be extremely helpful.

Get involved politically. Attend your local city/town council meetings, especially when library-related issues are on the agenda—and don’t forget the all-important subcommittee meetings, when budgets are being discussed. In addition, if your library has suffered from some of the “culture wars” issues so prevalent these days, don’t sit on the sidelines and let the angry authoritarians have their way. If there was ever a time to stand up to bullies, that time is now.

This completes my list of ten ways you can support your library. Perhaps a few more will come to your mind as you peruse this week’s compilation of quotations:

The library became the cathedral where I would come to worship and the stories were as precious to me as prayers. — Anita Anand

It isn’t just a library. It is a space ship that will take you to the farthest reaches of the Universe, a time machine that will take you to the far past and the far future, a teacher that knows more than any human being, a friend that will amuse you and console you—and most of all, a gateway, to a better and happier and more useful life. — Isaac Asimov

I had always imagined Paradise as a kind of library. — Jorge Luis Borges

A library doesn’t need windows. A library is a window. — Stewart Brand

A library, to modify the famous metaphor of Socrates, should be the delivery room for the birth of ideas—a place where history comes to life. — Norman Cousins

Librarianship is the connecting of people to ideas. — GraceAnne DeCandido

The library is an arena of possibility, opening both a window into the soul and a door onto the world. — Rita Dove

A library is a place where you can lose your innocence without losing your virginity. — Germaine Greer

A library in the middle of a community is a cross between an emergency exit, a life raft and a festival. They are cathedrals of the mind; hospitals of the soul; theme parks of the imagination. — Caitlin Moran

It’s funny that we think of libraries as quiet demure places where we are shushed by dusty, bun-balancing, bespectacled women. The truth is libraries are raucous clubhouses for free speech, controversy, and community. — Paula Poundstone

For source information on these quotations, and many, many others on the subject of LIBRARIES, go here.

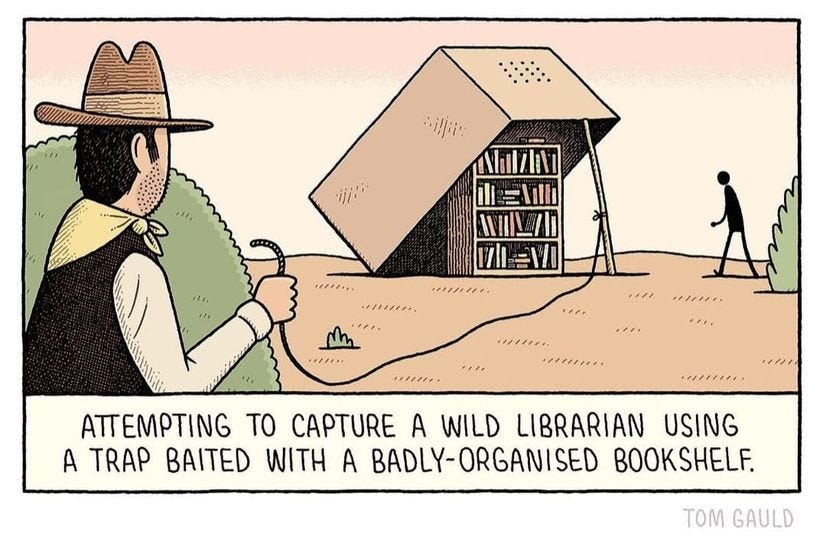

Cartoon of the Week:

Answer to This Week’s Puzzler:

Ray Bradbury (1920-2012)

Dr. Mardy’s Observation of the Week:

Thanks for joining me again this week. See you next Sunday morning, when the theme will be “Democracy.”

Mardy Grothe

Websites: www.drmardy.com and www.GreatOpeningLines.com

Regarding My Lifelong Love of Quotations: A Personal Note

Libriaries-one of the few remaining pillars of the hmmm..Civilization

andre hubert

I connected with every word in today's letter. If you are ever near Cleveland do come to any of our great county libraries, BUT the best independent or just the best ever, is the Twinsburg Public Library on Ravenna Road. It has all the things you wrote about and an exquisite used book store. Like all "Friends of the Library" book sales it is run be volunteers and stocked by donations from the community.The collection is eclectic. The volunteers are truly friends. We even have a gift counter with items from local crafters. It is loosely organized so browsing is essential. I do think Ray would have been a frequent shopper.