Dr. Mardy's Quotes of the Week ("Potential for Greatness")

November 5—11, 2023 | THIS WEEK'S THEME: “Potential for Greatness”

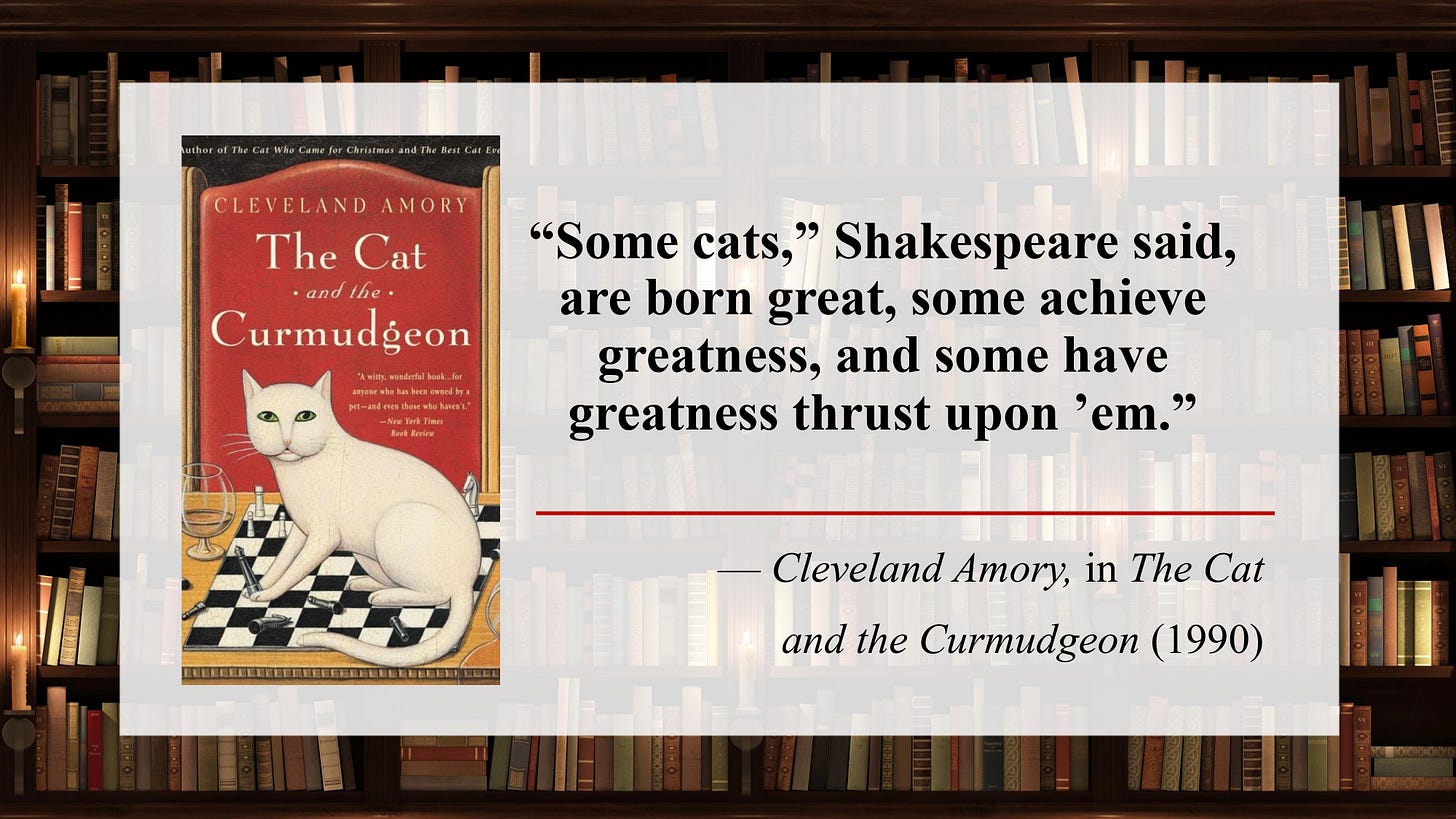

Opening Line of the Week

If you’re struggling to craft a memorable opening line for something you’re writing, consider tweaking a legendary quotation, as the clever Mr. Amory does here. In the book’s second paragraph, he continued:

“Actually, Shakespeare didn’t say that about cats, he said it about people. And I suppose there will be some purists out t…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dr. Mardy's Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.