Dr. Mardy's Quotes of the Week ("Sarcasm")

March 31—April 6, 2024 | THIS WEEK: “Sarcasm”

Opening Line of the Week

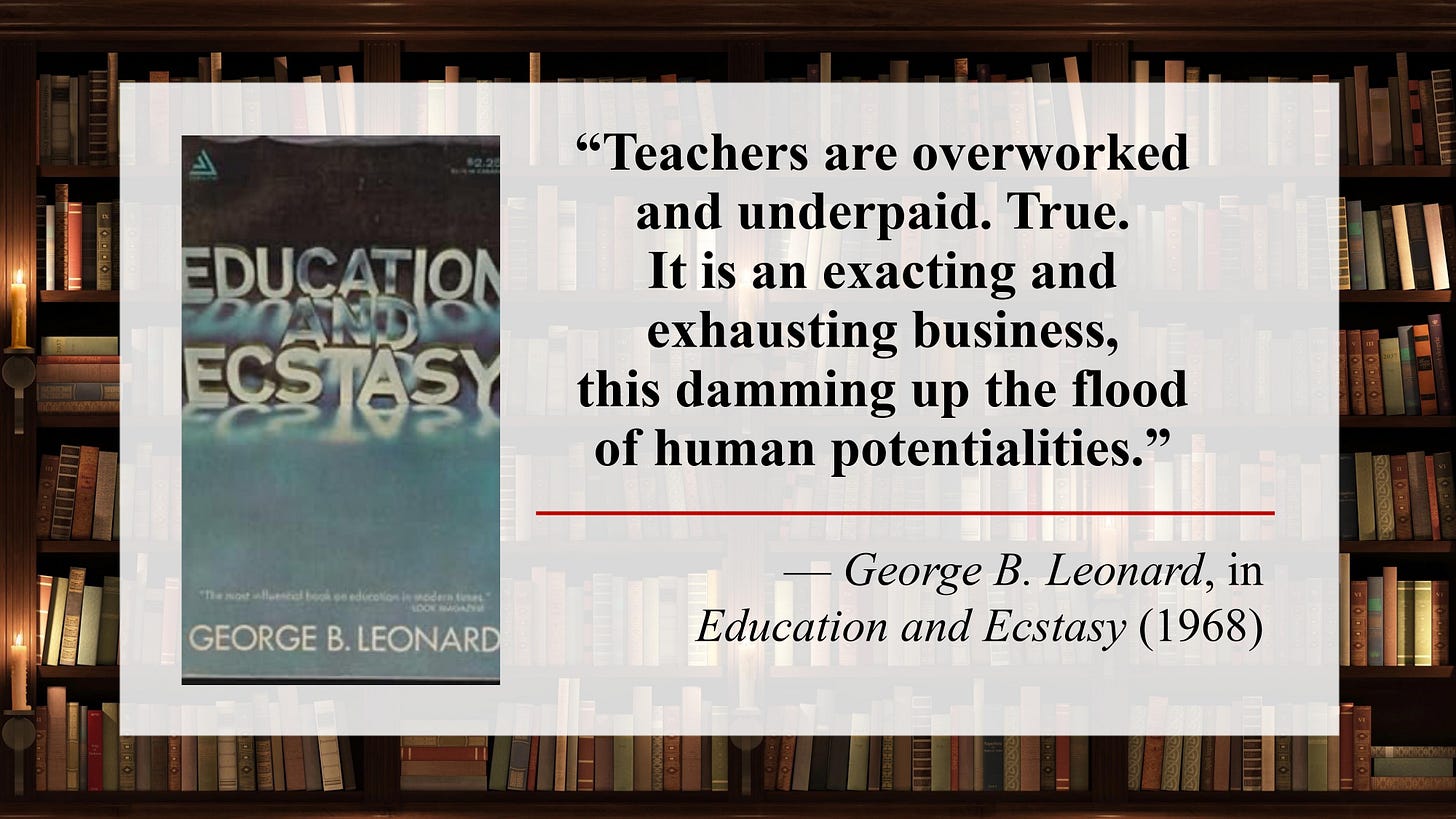

It is generally inadvisable to begin a book with a sarcasm-laced observation, but Leonard—a leader of the human potential movement as well as a critic of the educational establishment—was clearly trying to get people’s attention. In the first paragraph, he continued:

“What energy it takes to make a torrent into a trickle, to trai…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dr. Mardy's Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.