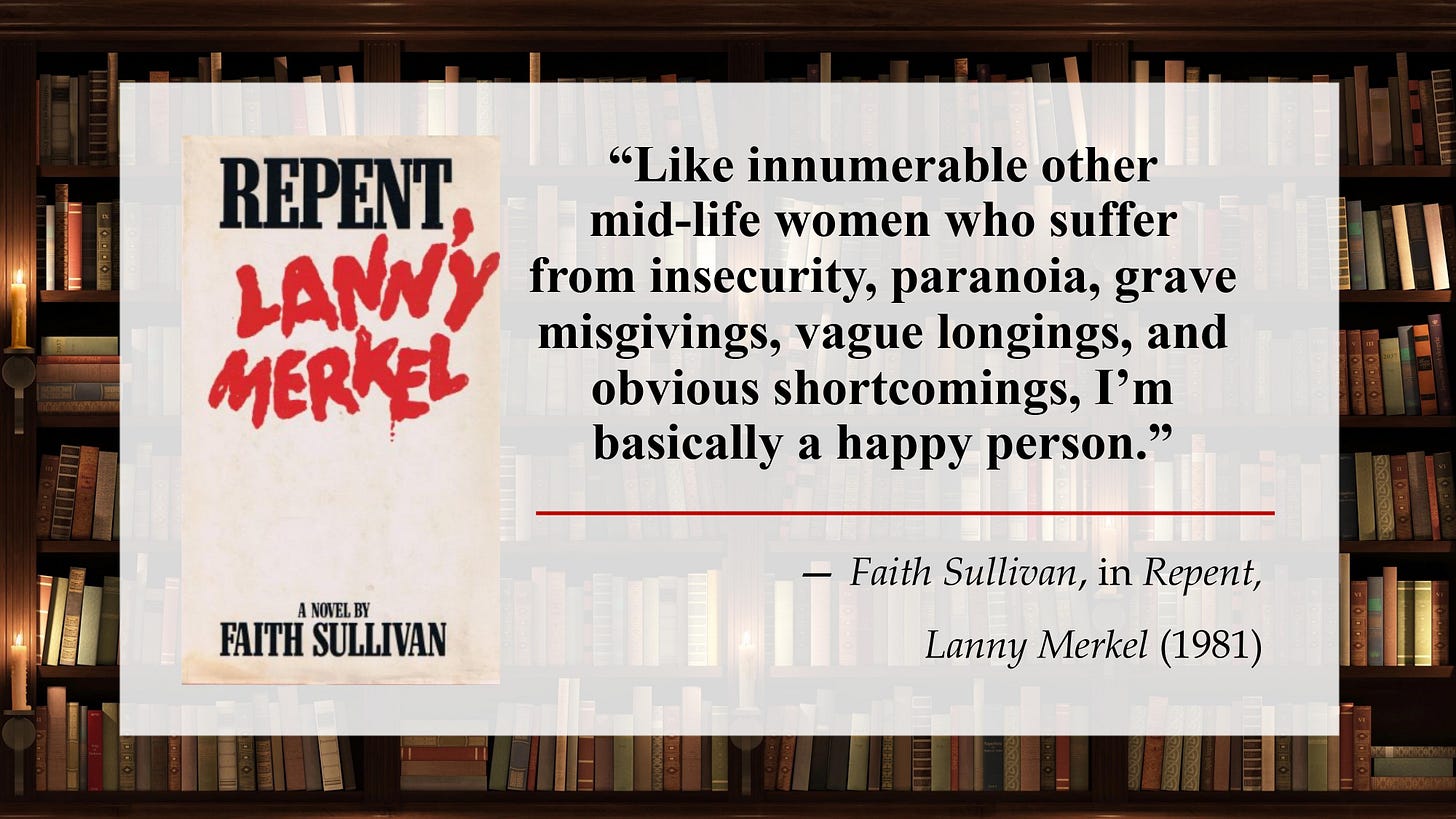

Opening Line of the Week

I love a great oxymoronic opening, and this one has been a personal favorite for more than two decades. The words come from narrator and protagonist Laura Pomfret, a middle-aged Minnesota mother and housewife whose life is upended when she receives an invitation to her 25th high school reunion.

As she thinks about attending what w…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dr. Mardy's Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.