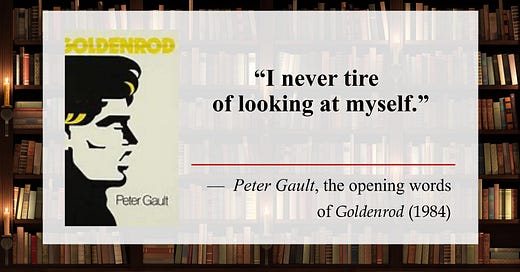

Opening Line of the Week

When I first came upon these opening words, I thought to myself, “Sounds like something Narcissus would say.” I also found myself wondering if the author had deliberately crafted the first sentence with the self-loving mythological figure in mind. Sure enough, he did. In the opening paragraph, the narrator continued:

“I can sta…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Dr. Mardy's Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.